Butt Anatomy: Gluteal Muscles and How to Build ‘Em

Butts are all the rage these days: on TV, in magazines, and behind retail store windows. And thanks to social media, we thoroughly know what butt muscles looks like — check Instagram if you’re still confused.

But a lot of us are fuzzy on butt anatomy: exactly what those globular lobes are and how they function.

If you’re interested in improving on your rear view, the first step is knowing exactly what those mounds of muscle are up to on a day-to-day basis; the better to ensure that they’re doing their job properly whether you’re at play, at work, or working out.

Here’s your butt anatomy primer.

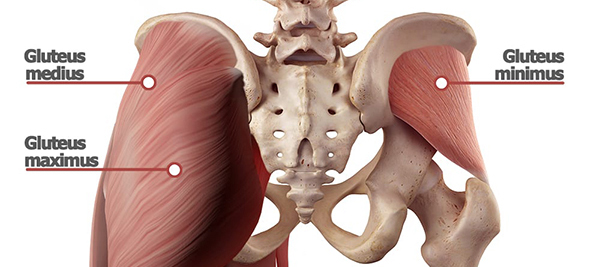

Which Muscles Comprise Your Butt?

Compared to, say, your knees, whose range of motion is primarily limited to one plane of movement, your hip joints are quite mobile, allowing your femurs to move in three planes: back and forth, side-to-side, and rotationally.

Here are the key posterior muscles that control those motions.

The star: Gluteus maximus

Function: There’s a reason why your glute max is often referred to as the strongest muscle in your body; like your other gluteal muscles, it helps rotate your thighs outward, but it’s also the one that’s most responsible for extending your hip, and therefore helping you maintain an erect posture.

As the largest muscle in the body, it’s capable of generating tremendous force.

No basketball player could dunk a ball, no running back could tear through the line, and no fitness enthusiast could squat or deadlift big weights without tons of help from the glute max.

Location: The glute max originates at your pelvis and sacrum and inserts in two places: your iliotibial band (a tract of connective tissue that runs along the outside of your thigh) and your femur, just below your butt cheek.

How to target it: Work all that glorious sinew with squats, deadlifts, lunges, and any other move that requires you to extend your hip.

Supporting cast: Gluteus medius

Function: Appearing just above and outside the rounded portion of your butt, the glute med’s primary job is to abduct your legs. It also aids in rotating your thighbones both internally and externally.

Location: This fan-shaped sheet of muscle originates along the top ridge of your hip bones and attaches to the greater trochanter — the bony protrusion on the outside of your hip.

How to target it: Work it directly with exercises like the clamshell or the banded lateral walk.

Supporting cast: Gluteus minimus

Function: The gluteus minimus is the medius’ little brother; its primary responsibility is to provide stability to your thigh while you’re standing on one foot.

Location: The glute min is similar in shape to the glute med, and lies directly beneath it.

How to target it: You can emphasize the glute min with side plank variations.

Bit players: Deep rotators

Lying beneath the much-admired gluteal muscles is an under-appreciated group of smaller ones called the deep lateral rotators. All of them originate at the back of your pelvis and attach to the top of your thighbone, wrapping around it like a flag around a pole.

As their collective name suggests, your deep lateral rotators rotate your thighbones outward, which you’ll recall is known as external rotation. You’ll rarely have much cause to consider these muscles unless something goes wrong with them.

Piriformis syndrome — inflammation, tightness, or spasms in the topmost rotator — is fairly common among both athletic and sedentary populations, and can cause radiating pain in the buttocks and hamstrings. Hip stretches can help.

What Do Glute Muscles Do?

Your glutes are responsible for several important hip joint movements.

Hip extension

Pulling your knee toward your chest is known as hip flexion; the opposite movement is called hip extension, and it’s among your glutes’ primary jobs.

Fully contracting these muscles draws your thighs behind you. Think of a sprinter in full stride: the glutes on her back leg are about as contracted as they get.

Hip abduction

Most people are familiar with the “innie-outie” groin torture machine at the gym: It’s the one you sit on, bracing the insides or outsides of your knees against the pads, then drawing them together or spreading them apart against resistance.

The glutes are responsible for that second action: bringing your femurs from an adducted (drawn-together) position to an abducted (spread-apart) one, as demonstrated in the clamshell exercise depicted above.

Hip rotation

The phrases “internal rotation” and “external rotation” sound fancy, but they just mean turning a limb toward (internal) or away from (external) your body’s midline. The glutes do both.

“In short,” says Trevor Thieme, C.S.C.S., “the glutes help move your legs and hips — and provide balance and stability — whenever you sprint, jump, climb stairs, or get up out of a chair.”