Why Are There So Many Conflicting Opinions in Fitness?

Follow health and fitness news long enough and you’ll notice an unsettling trend: even the best advice can be contradictory.

In any given week, one dietary expert might tell you that tracking calories is the key to weight loss, while another says to forget calories and count carbs instead. One fitness pro claims isolation exercises will make you big and strong; another swears they’re useless. Six months later, the camps switch, then switch again.

It’s enough to make you throw up your hands. All you want is clear, consistent advice on how to get lean, strong, and healthy. Is that really so hard?

In a word, yes.

Why There’s So Much Confusion in Fitness Advice

The latest studies say one thing; your trainer says another. Here’s why they don’t always agree — and why neither one is wrong.

Science doesn’t always align with practice

Science doesn’t always align with practice

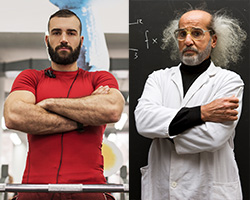

Putting aside the ill-informed advice of celebrities — whose fun-to-consume wisdom is the fitness advice equivalent of junk food — there are two primary sources of fitness information: scientist-researchers and trainer-coaches.

You’d think these two camps would get along famously. Exercise scientists work in labs, and coaches and trainers in gyms and on athletic fields, but both traffic in lifting percentages and running distances; both measure outcomes and track results; and both are looking for the best ways to improve human health and performance.

There’s a dividing line, however, between these two groups, who represent, broadly, the theory and the practice of fitness. “The mentality is different,” says Dr. John Rusin, CSCS, who, as both a physical therapist and strength coach, has a foot in both camps. Scientists are cautious and conservative, coaches more intuitive and improvisational. “That means the practice will always be years ahead of the science,” says Rusin.

It also means that sometimes trainers will be off base, or even flat-out wrong in their approaches. If the trainer has a large following, a practice may filter into common usage long before it has been vetted by science. They may use terminology that’s pertinent to their practice — such as a Pilates instructor telling people to “lengthen” or “elongate” their muscles as they work them — but that researchers will later show is physiologically impossible (muscles have a fixed length — you can’t make them longer). Or they may simply be working from outdated intel: Recent research suggests, for example, that excessive running can lead to heart problems, that abdominal crunches can be tough on your spine, and that behind-the-neck presses can damage your shoulder joints. Yet many a qualified, well-intentioned health professional, pulling from older research or personal experience, will tell you otherwise.

Technically, everything “works”

Technically, everything “works”

Exercise is medicine. It improves your mental health, cardiovascular fitness, and muscle tone. It aids the functioning of your organs, boosts your mood, and, of course, helps you look and feel immeasurably better. The benefits of exercise, to every system in the body, are so varied and consistent that doctors are fond of saying that if you could prescribe it in pill form, it would break every sales record.

And that’s all kinds of exercise: cycling, lifting, jogging, dancing, brisk walking, even gardening. Anything that elevates your heart rate that you can keep up for 30 minutes or more qualifies. And as far as your doctor is concerned, so long as you’re doing something — anything — for that long, most days of the week, you’re doing great.

So if you hear anyone — scientist, coach, trainer, or your Aunt Joan the gym teacher — say that their exercise program will make you leaner, stronger, and fitter, they’re probably right… if you compare what they’re recommending to doing nothing at all. Many of the benefits of exercise come from following very basic parameters. It’s when you go beyond those parameters in pursuit of higher levels of fitness and specific athletic goals that training becomes more nuanced — and the likelihood of receiving conflicting advice from various sources increases.

Exercise is inexact

Exercise is inexact

“There’s almost nothing more subjective than human movement,” says Rusin. Let’s say, for example, you’re an exercise scientist trying to measure the effects of push-ups performed three times a week. You bring in some willing participants and stand over them while they bang out their reps.

How strict should a researcher be when counting reps? What if a test subject flares her elbows instead of keeping them close to her body? What if her hips sag slightly? What if she doesn’t lower herself quite far enough? Does the rep count?

Since coaching affects performance, says Rusin, lab technicians are forbidden to offer suggestions on how to improve technique once testing begins. The result can compromise many subjects’ results. So while counting reps may seem simple — it’s not. “It’s about the hardest thing in the world to quantify,” says Rusin.

Add to that the difficulty of controlling factors like your subjects’ diets, sleep, mood, and mental state, and it’s easy to see why studies frequently conclude with the maddening statement that “more studies are necessary.”

Even if you are able to control the dozens of variables in that one exercise in your study, there’s no guarantee the designer of the next study will control those variables in exactly the same ways. Much less that your average fitness consumer who attempts the program at his or her local gym will do so. Very quickly, it can become an apples-and-oranges situation.

Meaning results will vary. And the experts — whether they’re scientists or coaches — will have many different opinions about even simple things, with scientists often concluding that certain practices work in a lab, and coaches determining that those same practices fall apart in the real world.

This is not to say that it’s impossible to draw conclusions about exercise — just that it’s rarely, if ever, easy.

Everyone is different

Everyone is different

Not every research study — or every workout — applies to everyone. “Certain techniques work better for certain populations,” says Jonathan Mike, Ph.D., CSCS, associate professor of exercise science at Lindenwood University in St. Charles, Missouri. For fat loss, he says, both steady-state cardio and interval training can work — but one or the other might be appropriate for a particular person depending on factors like age, injury history, fitness level, and proficiency at a given exercise.

Beyond demographics, there are also differences — sometimes extreme differences — in the way people respond to exercise. A 2001 study demonstrated different people can achieve entirely different results from the same exercise program. And while most see average results, the study found some people see exceptional results; researchers call these lucky folks super-responders.

Then there are those who fall on the other side of the ledger, dubbed non-responders by the study authors, who claimed that this unfortunate group didn’t improve at all. While more recent studies in 2015 and 2017 dispute the possibility of non-response to exercise, they still found that those labeled non-responders needed to work much harder to get results.

Short of elaborate DNA testing, there’s no way to know whether you’re an average responder, a super-responder, or a low-responder to any particular program unless you try it. Fortunately, more recent research has also found that non-responders to some types of exercise respond well to others. So if you don’t get the results you want from one type of training, keep looking. The key is to figure out what mode of exercise best suits your taste — and your body — and stick with it.

Numbers can be misleading

Numbers can be misleading

At its best, science can parse superstition and subjectivity from fact, shedding light on hard evidence and casting human error into darkness. But science is still a human endeavor, which means personal bias can affect even the most careful research.

One key factor: the profit motive. “Research is not cheap,” says Rusin. “Most university-based research is privately funded.” As a consequence, large-scale studies are often conducted with corporate interests — rather than human ones — at heart. That doesn’t make the results of those studies entirely worthless, but it can certainly put a thumb on the scale when results are not entirely persuasive.

“Laypeople have no idea about how statistics are broken down and analyzed,” says Rusin. Having designed and conducted a study himself, and read and analyzed hundreds more, Rusin explains, “Any single study can be manipulated, 110 percent. You can sway it either way.”

Of course, many coaches and trainers — famous and obscure alike — are influenced by the profit motive as well. “Many individuals skew science to make their product look the best when in reality it’s good marketing, not a good product,” says Dr. Mike.

That’s why it’s so important for fitness consumers to find trainers, researchers, and coaches they can trust and who straddle both worlds — staying abreast of the science while maintaining a thriving personal practice as well. Even then, there’s no way to eliminate the risk of bias entirely.

“There’s evidence out there that supports every conclusion you can think of,” says Rusin. “Try to sift through it all and you have paralysis by analysis.”

The best researchers, says Dr. Mike, are fitness enthusiasts themselves, who understand the types of questions that are important to the average gym-goer. “In the last three to five years,” he says, “there’s been a good transition to more field-based training that has a more effective transfer to trainers and coaches.”

Similarly, the best coaches, says Rusin, pull from the world of science, boiling new research down to something they can teach to others, and making adjustments when science shows them a better way. Perhaps most importantly, they teach and present everything they’ve learned in a style that motivates people to throw themselves into it — and to keep coming back, week after week. “That has nothing to do with the X’s and O’s of programming,” says Rusin. “It’s the art of coaching.”

So Who Can You Trust for Fitness Guidance?

At the end of the day, you need to find your own way. Exercise scientists, celebrity coaches, and the trainer at your local gym can certainly offer advice and encouragement, but with so many conflicting opinions in fitness, you also need to take into account your personal tastes and your body’s unique responses to given exercises. The best approach for the average fitness consumer, then, is to become something of a scientist-coach yourself, respecting the tried-and-true principles, experimenting with promising new ones, absorbing what’s useful, and discarding what isn’t.

With that in mind, here’s some advice that will always endure when trying to refine your fitness regimen.

Consider the source

Get your information from authorities that boast both scientific and practical expertise. As Dr. Mike and Rusin say above, the best researchers are fitness enthusiasts and the best coaches emphasize science.

What are their credentials? What do they stand to gain? How long have they been around? Once you’ve determined that a source is credible, find another one that says the same thing, and read beyond the headlines.

Note the activities your body responds to most

The way one person reacts to a given activity is one thing — the way you react to it is another. Whether it’s running, cycling, swimming, weightlifting, or any of the dozens of workout programs offered by Beachbody, some trial and error will be required to identify the modes of exercise to which your body adapts best.

Learn how to pick a Beachbody program here.

Choose exercises you’re actually motivated to do

Motivation and mindset play huge roles in any exercise program. In fact, says Rusin, “It supersedes everything. Motivation and the capacity to work hard are the biggest factors in determining the success of an exercise program.”

The science behind a program is certainly important. But once you have a solid program in place, success or failure depends less on science than it does on you.

Not only are Beachbody’s workout programs based on the latest exercise science, they’re exhaustively tested under real-world conditions to ensure the safest, most effective results. You can stream all of those programs on Beachbody On Demand, via your TV set-top box or mobile device. Sign up to become a member now!