Presidential Physical Fitness Test: Can You Pass It Now?

If your school days are behind you, you probably remember—in disturbing detail—the gym-class rite of passage: the Presidential Physical Fitness Test.

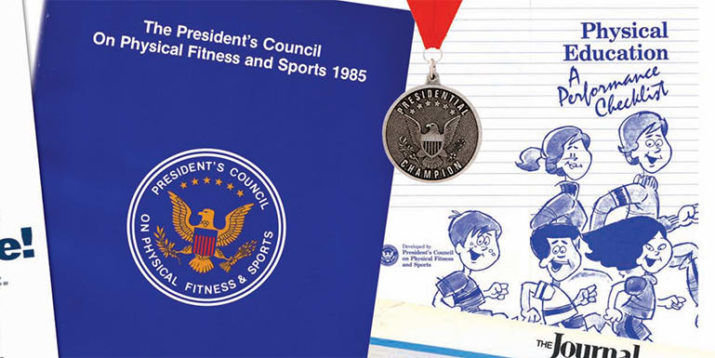

For all of you folks lucky enough to avoid this public school tradition, this battery of tests (including the dreaded trio of “ups”: the sit-, the push-, and the much-reviled “pull-“) was given twice a year to schoolchildren starting in the late ’50s and concluding (thankfully) in 2012.

Picture a hoard of eight-year-olds staggering through a cross between a cattle show and the NFL combine and you’ll have a pretty good idea of what the test was all about.

I got to wondering recently: What on earth were we thinking?

Whose Bright Idea Was It, Anyway?

Turns out the tests go all the way back to President Dwight Eisenhower, who was alarmed by a report that revealed nearly 60 percent of American kids failed one or more tests of fitness, compared to less than nine percent of their European counterparts.

The original tests were very basic: If you could do a single sit-up and a single leg lift, you passed. Eisenhower was troubled, not least because the findings implied that our kids were unfit for military service, hence, the slightly patriotic flavor of the whole endeavor.

I, for one, swallowed the whole thing hook, line, and sinker back in the early ’80s. I even trained for it, banging out sit-ups and shuttle runs in the backyard whenever the mood struck.

An apathetic athlete, I was middling at dodgeball and mediocre at freeze tag, but boy, could I ever nail those Presidentials. If memory serves, I bested over 90 percent of the country’s 10-year-old population with my 60-second score on the flexed-arm hang. Take that, communists!

Are They Effective Fitness Tests?

Now that I’m a fitness pro, I’ve come to recognize the Presidentials as essentially flawed. Because you were being pitted against other kids in your age group nationwide, success depended not just on being “fit” but on being fit-ter than other kids.

As a result, a good many kids outright failed—and everyone in the class had a pretty good idea of who those kids were. Then there was the public humiliation factor: It felt good to announce to my PE teacher that I’d hit 62 reps in the sit-up test, but it must have felt terrible for others to call out 30, or 20, or zero.

Through the magic of the Internet, I tracked down Debby Franzoni, the same P.E. teacher who administered those tests to my elementary-school class back in the ’70s and ’80s. She agreed the test had its problems: “You never really got out of the percentiles you were first in because normal people do not practice to the point of improving enough to change percentile scores,” she said.

But setting a high bar was standard operating procedure for P.E. teachers back then, says Franzoni. “We were taught to teach to those who got into the 85 percent or above because they were the ones going on the athletic teams. The ones from 50-85 would be good at intramural level and the ones below that would do best in French Club.”

Changing Fitness Standards

In 1987, everything changed, says Franzoni—including the tests. “Instead of being pitted against each other, kids were tested to see if they fell within a healthy standard in each component,” she says. In other words, it was no longer about identifying exceptional performers, but about improving the health of the entire class.

Nowadays, the fitness test of our youth has been replaced with overall health and fitness programs like Let’s Move and the Presidential Youth Fitness Program, which has been touted as “more than a test.”

In her remaining years as a P.E. teacher, Franzoni increased her students’ average pass rate on the new tests from 50 to 90 percent. (And for the future psychological well-being of kids everywhere, I say, “Thank God.”)

Then vs. Now

To a fitness nerd like myself, however, the allure of those original, uncompromising fitness standards still looms large. That’s why on a recent Sunday morning, I put on my sweat suit and headed to the track, determined to put my fitness-obsessed 45-year-old body to the test (again). This is how I did:

Max pull-ups: 20 (over 85th percentile)

V-sit-and-reach: 7.25″ (over 85th percentile)

Sit-ups (one minute): 53 (just below 85th percentile)

30-foot shuttle run: 9.6 seconds (just below 50th percentile)

One-mile run: 8:30 (pathetically below 50th percentile)

As much as I hate to admit it, these scores are fairly accurate reflections of my athletic strengths and weaknesses. I’ve always had decent upper-body strength, so my sit-up and pull-up scores were expected. Over the last few years, I’ve worked to develop good flexibility, so my sit-and-reach score felt right, too.

Running speed and explosiveness were never my strong suits and haven’t been training priorities of late, so those results are predictably subpar. But maybe that’s because I’ve fallen into a common fitness trap: playing to my strengths while avoiding my weaknesses.

(FYI: If I’d turned in these scores as a teenager, I still wouldn’t have gotten the award, which is disproportionately upsetting to a guy who, by this point in his life, should have more important concerns than outrunning teenagers.)

But the good thing about this test—and any fitness test—is that it gives you something to track and improve on, and in that sense, Eisenhower and Co. were onto something.

See you at the track.